Haunted by trauma

Six months ago, a dam collapse killed 300 people in Brumadinho, Brazil. Survivors now face a new challenge: a severe mental health crisis

The crisis

Six months after a dam collapse killed nearly 300 people in Brumadinho, in the heartland of Brazilian mining, the population is now facing a new crisis: a surge in severe psychiatric disorders.

Anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and even suicide attempts are now part of the routine of the once bucolic town.

The number of people assisted by Brumadinho’s Mental Health Department doubled in the last three months. Distribution of drugs to treat psychiatric disorders, such as anxiolytics, grew by 80% and antidepressants by 60%, according to local authorities.

Even without official statistics available yet, Kênia Lamounier, the psychologist in charge of the Mental Health team in Brumadinho for the last 15 years, says the signs for the increase in usage of such meds are obvious.

Most cases are related to alcohol and drug abuse, trouble sleeping, nightmares, worrying excessively about safety, or strong physical reactions like trouble breathing when reminded of the disaster they survived.

“Gradually, some people manage to be resilient and get back to their lives and routines, but for some, it does not go away. We are now entering a phase when we start to identify which cases are turning into a chronic condition, an illness.” (Read more at 'The people' section).

A recent disaster

This post-disaster scenario is described by several studies about populations affected by a trauma. One of them was made in 2017 by the Health and Vulnerability Research Center at the Minas Gerais Federal University, with victims of other dam ruptures in Brazil, in the city of Mariana, in 2015.

The city of Mariana was vanished after a dam collapse in 2015. (Credit: Rogério Alves-TV Senado-Creative Commons)

The city of Mariana was vanished after a dam collapse in 2015. (Credit: Rogério Alves-TV Senado-Creative Commons)

According to the report, two years after the accident, 28.9% of victims had depression (3.5 times higher than expected in the general population), 32% had Anxiety Disorders (3 times higher), and 12% had Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In children, the percentage has reached 83%.

The risk of suicide was identified in 16.4% of the interviewees – a rate three times higher than the national average.

Maila Neves, a professor at Minas Gerais Federal University and this research coordinator, warns that the consequences from the disaster can be even more severe for Brumadinho's population than Mariana’s due to the number of victims.

Another relevant aspect in the Brumadinho case is the age of those killed.

“When we talk about the death of young people, the Vale workers, for example, there are orphans. The loss of parents in such a traumatic situation can bring long term disruption to these children.”

Hopelessness

According to the expert, hopelessness about the situation and the possible impunity help aggravate the psychological disorders.

In Mariana, three years later, no one has yet been arrested and the case is pending trial. The reconstruction of the destroyed houses in a new district is delayed and the deadline for completion is 2020. Meanwhile, families live on monthly financial aid, without compensation.

Psychologist André Luiz Freitas Dias, also from the Minas Gerais Federal University, says the prolonged suffering of having to deal with the company that caused the harm, both in Mariana and in Brumadinho, worsens the situation because the victim is subjected to contact with the aggressor.

Creuza Sobrinho, a Brumadinho resident who lost two siblings and dozens of other relatives and friends (see more in The People section) said: “I attended only one meeting with Vale (the company) and never came back. I can’t listen to anything they have to say. They ruined my life.”

Suicides among the risks

In a small town such as Brumadinho, with 40,000 inhabitants, it is hard to walk around and not find anyone who hasn't lost a family member, a friend or a neighbour buried in the 11.7 million cubic meters of deadly toxic mud.

The emotional scars are deep and, at least three of the interviewed residents, who asked not to be identified, experienced a case of suicide attempt within their close circle of friends or by a family member. (Read more at ‘The people’ section) Mrs Lamounier confirms her team of psychologists assisted suicidal patients.

Professor Marcelo Arinos Drummond, from the Public Health School of Minas Gerais, explained there are three major conditions expected in Brumadinho’s population after six months: post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression, which can escalate to suicide attempts.

Professor Marcelo Arinos Drummond, a mental health expert explains the most likely disorders to be identified in Brumadinho six months later. Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

It can get worse

Rodrigo Chaves Nogueira, a psychologist and Head of Mental Health Department in Brumadinho for nearly three decades, explains that even after the mudslide, Vale continues to cause damage.

He says there will be consequences from the distribution of financial compensation without monitoring the consequences of such money influx in the economic and social dynamics of the small city.

“The collective grief we observed right after the disaster is suspended. Now we see an excessive euphoria with the large amount of money paid by Vale and the monthly pension they are providing. People are living in the false sensation that everything is fine and are not processing their feelings”.

As a result, the Health Secretary of Brumadinho expects cases will be aggravated in the beginning of 2020, a year after the disaster. Mr. Nogueira explains the population will experience a “pathological grief”, a disorder that afflicts those unable to work through their grief despite the passage of time.

The main challenge now is keeping those affected under treatment in a long term basis, since many disorders only manifest months or even years after the first traumatic event.

In such wide scale disasters it is important to identify mental health issues early, still psychologists warn that Vale is obstructing such efforts.

Vital information is still kept under wraps, Mrs. Lamounier says.

"We don't know where people displaced are accommodated, how many orphans are there. How am I supposed to find and treat these people?"

The team plans to go to court to make Vale share details about the victims and how they are being assisted.

Vale did not respond to any interview request during this reporting.

The effects of the destruction caused by the mud are physical but also symbolic.

Complaints about the suffering, fears, anxieties and uncertainty about the future are increasingly present in the comments of the victims.

In this special report, you can read some of their stories:

The people

PSYCHOLOGIST, MOTHER OF TWO, WIDOW

Kênia Lamounier

"This is worse than a horror movie. Horror movies have an ending"

Kênia Lamounier, 52, is a psychologist. She has been treating people for over 15 years. But no challenge she has ever faced during her career would have prepared her for what she witnessed in Brumadinho.

She experienced first-hand the trauma of losing someone in a disaster. Her husband, Adriano Lamounier, a Vale employee for 17 years, perished in the dam collapse.

“It’s unbelievable that a company would execute their own employees like that. Vale is a murderer company.”

Despite her pain and rage, she had the tough task of reconciling two roles: the grieving widow and the psychologist in charge of the mental health support team in Brumadinho.

Mrs. Lamounier stayed away from the office for a month, the same time it took to find her husband’s body. Her return to duty was not easy. Still isn’t, she says with a cracked voice. However, her mission is more important.

“People find it easier to open up to me. They tell me: ‘You know what I'm going through’. It's a kind of mutual help.”

Six months after the disaster, she describes the current mental state of residents as that of a “war zone returnee”. Patients, in a growing number, are looking for support with symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, drug and alcohol abuse, and suicidal behaviour.

“This is worse than a horror movie. Horror movies have an ending.”

SMALL FARMERS, SURVIVORS

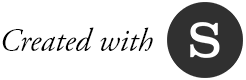

Cleusa Gomes & Edmilson Leal

“I’m constantly stressed out, thinking I'm about to die”.

Cleusa Gomes, 53, and her husband Edmilson Leal, 52, escaped, but waited a week to be rescued in the farm they worked

Cleusa Gomes, 53, and her husband Edmilson Leal, 52, escaped, but waited a week to be rescued in the farm they worked

It was lunchtime when Cleusa Gomes, 53, a resident of Parque da Cachoeira district, in Brumadinho, heard the neighbors, in despair, screaming “something bad” had happened. She was making artisanal cheese when she was forced to run, leaving everything behind, including her shoes.

She only stopped on the top of a mountain nearby to see a sea of mud engulfing the valley as well as part of the farm where she and her husband, Edmilson Leal, 52, used to work the last five years. There was no way out.

They were isolated with no electricity or drinking water. The only cell phone was dead.

“We slept in the forest for two nights, fearing another dam collapse would hit the farm and kill us”.

They were found by a rescue team flying over the farm in a helicopter a week later. Supplies started to come by air, as they refused to leave the farm, their animals, and their beloved eight dogs.

In the following weeks, workers built an alternative road granting access to their neighborhood and they were finally rescued by truck.

Mrs. Gomes, who is under psychological treatment for nearly 16 years, takes controlled medication to reduce her anxiety levels. She says her psychological state deteriorated since the disaster. Sleeping is challenging. Her nights are interrupted by nightmares, panic attacks, sweating, hyperventilation, and nasal bleeding.

“I’m constantly stressed out, thinking I’m about to die”.

MANICURE, LOST 2 BROTHERS, 1 SISTER IN LAW, 5 COUSINS, 20 FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS

Creuza Sobrinho

"Vale didn't kill only my brothers. It killed me inside too."

Creuza Sobrinho, 53, says her family is torn apart after the disaster

Creuza Sobrinho, 53, says her family is torn apart after the disaster

The once busy family group on Whatsapp has never been this silent.

Before the disaster, it was used to send jokes and schedule the next weekend barbecue, which always happened at Creuza Sobrinho's place. In the last six months, though, the family only reunited for funerals.

"The family is torn apart. It's over.”

Mrs. Sobrinho and her six siblings from a low-income background were raised in the surroundings of the now collapsed Córrego do Feijão Mine, Brumadinho.

The community ties were strong. "My father was an alcoholic and my mother left when I was 8 years old. So, I raised my brothers with the help of neighbors and friends".

The picture of Mrs. Sobrinho's family in the last barbecue they had is in the Whatsapp Group profile. (Credit: courtesy of Creuza Sobrinho)

The picture of Mrs. Sobrinho's family in the last barbecue they had is in the Whatsapp Group profile. (Credit: courtesy of Creuza Sobrinho)

As Vale is the main employer in the city, the family always saw the company as a dream job.

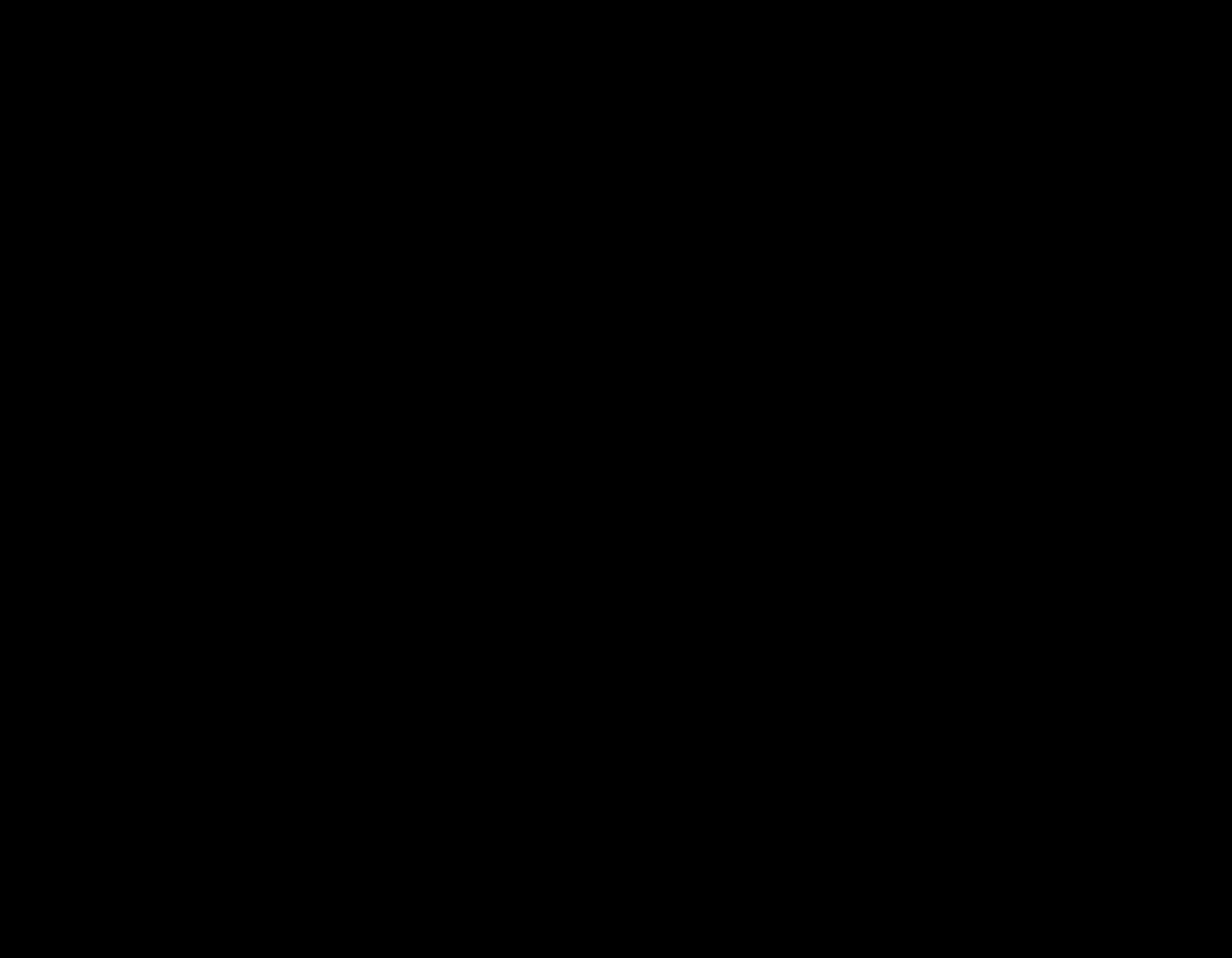

Miramar, 48 and Ruberlan Sobrinho, 50 managed to get there. Both were Vale employees and died when the dam burst, alongside with a hundred other colleagues.

Miramar, 48, and Ruberlan Sobrinho, 50, were both Vale employees killed in the disaster in Brumadinho (Credit: courtesy of Creuza Sobrinho)

Miramar, 48, and Ruberlan Sobrinho, 50, were both Vale employees killed in the disaster in Brumadinho (Credit: courtesy of Creuza Sobrinho)

It took eight days to find the first and 75 days to recover the body of the latter. Their funerals weren't enough to find closure.

“We couldn't look at their faces and say goodbye properly. The coffins were sealed.”

The force of the mudslide tore their bodies apart.

Mrs. Sobrinho is seeing a psychologist, taking antidepressant and sleeping pills. Her case is worsening and she is now being recommended to a psychiatrist.

"Vale didn't kill only my brothers. It killed me inside too. I lost the will to live. Whatever we do doesn't make much sense."

HOSTEL OWNER, MOTHER OF TWO, WIDOW

Angélica Firmino

"I just feel numb all the time, but keep moving on for the kids' sake"

For Angélica Firmino, 41, the colours on the wall of her small business, the ‘Hostel LARes’ in Brumadinho are now just a reminder that, at some point, life was good.

Only two years ago, she personally designed the vibrant space with cheerful drawings and trendy decoration to host her guests: tourists visiting the famous Art Museum in the city, called Inhotim.

Mrs. Firmino family: her husband, a Vale employee, was one of the victims of the disaster

Mrs. Firmino family: her husband, a Vale employee, was one of the victims of the disaster

“We may need a fresh start. I haven’t decided what I am going to do yet, but all I want is the best for the girls.”

Her children are receiving psychological support at school. But not Mrs. Firmino. She says right after the disaster, she requested assistance from Vale, but they never returned her calls.

She had found her own way to deal with the pain. "I just feel numb all the time, but keep moving on for the kids' sake."

PATAXÓ HA-HA-HÃE INDIGENOUS LEADER

Angohó (Célia Pereira)

"We had four suicide attempts in our village after the disaster"

Miles downstream from where the dam collapsed, the small indigenous village, called Naô Xohã, faces doubts about its very existence. The Paraopeba River, the center of life for them, runs dark with mining waste. It cannot be used by the 150 people community for fishing, bathing or anything else.

Angohó (Célia Pereira), one of the leaders of the Pataxó Ha-ha-hãe people, explains how central the river is to their life: "The river is our source of life. When someone is sick, we perform the healing rituals in the river. Now we are the ones who will have to cure it of its disease."

Brazil’s indigenous affairs agency Funai and some NGOs are helping them by supplying some food and potable water. But not all the health risks are physical.

"We had four suicide attempts in our village in the last couple of month -- two women and two men. People are hopeless the river will ever recover, the kids are sad they can't bath there."

There is no psychological support for them.

RETIRED RESIDENT, LOST NEIGHBORS AND FRIENDS

Célia Pereira

"My 85-year-old mother had to run to survive"

There were six months since the last time Célia Darte, 57, visited her mother's house, in Parque da Cachoeira. She shudders when she remembers what has happened there.

"My mother is 85 years old. She was sitting by the pool with my sister and my brother-in-law when they heard a loud noise. The trees were going down. She had to run to survive".

It's still possible to see destruction trail. Where there's a thin green grass today, it was all toxic mud on January.

The torrent invaded the river, advancing towards the back of the property's area and filling the pool.

The back of the house has been destroyed by the force of the mudslide. (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

The back of the house has been destroyed by the force of the mudslide. (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

Mrs. Manoelina Darte, Célia's mother, can't give interviews, she says. Revisiting the trauma is prejudicial to her already degraded emotional state.

Since the disaster, her daughter says she is not the same. She doesn't smile, has trouble sleeping, her blood pressure levels and diabetes worsening.

The elder left the house she used to live in the last 30 years and is now living with family members. The house was a synonym of joy for the family and the destination of grandchildren during holidays.

"The mud crushed our good memories".

João Carlos Neto, 56, Mrs. Darte's husband looks at the cleared woods and recalls what the house meant to the family:

João Carlos Neto visited the destroyed house of his mother-in-law for the first time six months after the disaster. Memories were vanished by the mud. (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

RESCUER

José Fernandes

"I found five bodies

and countless body parts"

Rescuer José Fernandes proudly shows the medals he was awarded for his volunteer work (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

Rescuer José Fernandes proudly shows the medals he was awarded for his volunteer work (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

José Fernandes, 54, is a rescuer. He wasn't on duty when the dam collapsed, but felt compelled to volunteer and jumped into action.

He spent six days in a row in the frontlines, helping to rescue bodies buried in the mud.

"I've found five bodies and countless body parts."

The force of the torrent broke bodies into pieces. Rescuers had to deal with brutally graphic images.

Mr. Fernandes says the constant helicopter’s noise and the strong smell of rotten bodies made him decide it was time to stop on the sixth day.

"I couldn't keep on doing it. I'm lucky that I am emotionally strong, but I saw several colleagues having a breakdown".

He is not receiving any psychological assistance.

When asked how he is doing, he answers he is fine. Three times.

The disaster

A red wave of toxic mud

The collapse of Córrego do Feijão Mine occurred just after noon on January 25th, in the city of Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Brumadinho is located in the center of Brazil mining area (Credit: Google reproduction)

Brumadinho is located in the center of Brazil mining area (Credit: Google reproduction)

Dams like the one that collapsed in Brumadinho are, in essence, lakes of thick, semi-hardened mud consisting of water and the solid byproducts of ore mining, which are known as tailings.

The deluge of toxic mud first hit the mine's administrative area, where over a hundred of the mine's employees were having lunch.

The torrent of 11.7 million cubic meters then stretched for five miles, crushing homes, offices and people. According to calculations, the speed of the mud was nearly per hour when leaving the dam and about 20 km/h on its arrival in the neighbourhoods nearby.

The exact moment when Córrego do Feijão Mine dam collapses was recorded by the CCTV system. In the end of the video, it is possible to see people trying to escape. (Credit: Courtesy of Vale)

The exact moment when Córrego do Feijão Mine dam collapses was recorded by the CCTV system. In the end of the video, it is possible to see people trying to escape. (Credit: Courtesy of Vale)

As this is reported, 278 victims were recovered, including two pregnant women with their stillborn babies.

Six months on, bodies are still being found.

And 22 families are still waiting to bury their loved ones, in an endless grief.

During the reporting in Brumadinho, one of the last victims were found: Evandro Luiz dos Santos, a Vale employee. His funeral service was on July 7th (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

During the reporting in Brumadinho, one of the last victims were found: Evandro Luiz dos Santos, a Vale employee. His funeral service was on July 7th (Credit: Elisângela Mendonça)

The search for victims

Images: Courtesy of Minas Gerais Rescue Team (a day after the collapse - 26/01/19)

The silence

The company's silence

Giant Vale S.A., the world’s largest iron ore producer, is the company in charge of the collapsed dam.

Vale has yet to admit any responsibility. Federal and state prosecutors in the state of Minas Gerais are conducting criminal investigations.

Despite the efforts during the reporting, Vale declined all interview requests.

Compensation

This month, Vale has agreed to pay out £86m ($107m) in collective moral damages and £150,000 ($186,000) to each of the close relatives of the victims: partners, parents and children of victims.

It happened again

This is the second time the company is involved in this kind of disaster.

Over three years ago, in the city of Mariana, located in the same state as Brumadinho (Minas Gerais), there was another dam collapse. The event is considered the biggest environmental disaster of Brazil's history.

The burst of the dam unleashed 60 million cubic meters of iron ore waste and mud — the equivalent of 21,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The onslaught flattened neighbouring towns, such as Bento Rodrigues, and poured into the Doce River, killing 19 people and destroying 600 family homes.

The disaster was attributed to a severe lack of preparedness and oversight by the companies managing the project, as well as to insufficient regulation of Brazil’s mining sector.

The criminal investigation about that disaster has not led to any convictions so far.

The city

Six months later, the reconstruction

Driving in the surroundings of Brumadinho downtown looks like most of small towns in the countryside of Brazil: green, nice and quiet.

Credit: Luiz Guilherme Dias Fernandes

Credit: Luiz Guilherme Dias Fernandes

In this case, though, the silence is broken at least every hour by the train, loaded with minerals extracted from the other still active mines of the city.

Credit: Elisângela Mendonça

Credit: Elisângela Mendonça

Mining industry, after all, accounts for 4% of Brazil's GDP and 21% of what the country exported last year, according to official figures.

The city's roads resemble a construction site with trucks moving back and forth day and night. Most of them involved in the collection of the mud spread by the dam.

Credit: Elisângela Mendonça

Credit: Elisângela Mendonça

The scars left by the horrifying day in January in the residents, though, can still be spotted around the city. "Killer Vale" is written in graffiti in several walls.

Credit: Luiz Guilherme Dias Fernandes

Credit: Luiz Guilherme Dias Fernandes

An improvised memorial displays hundreds of white laces tied to a bridge in the entrance of the city. They wave as the wind flows carrying the names of the victims.

Most of them celebrate the victims and how they are missed -- a portrait of a city shredded into pieces, suffering from deep emotional wounds.

The only certainty is the hunger for justice. "This can't be forgotten so it will never be repeated", one of the laces say.

Credits: Production & Reporting: Elisângela Mendonça, Images & Videos (when not previously mentioned): Luiz Guilherme Fernandes, Creative Commons, Bombeiros MG, Funai, Agência Brasil, TV Senado.